Aszanckie rytuały przejścia

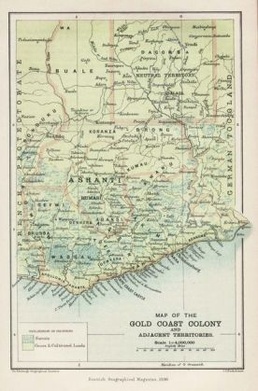

wikipedia (PD)

Kraj Aszantów (dzisiejsza Ghana) - mapa z 1896 r narysowana przez Johna George'a Bartholomewa

Afrykanie nie dbają o jednolitą skalę czasową, dlatego ich miara czasu jest tak zróżnicowana a cykle niekoherentne. W Afryce czas i środowisko wypełnione są religijnym sensem.

[1] A. Szyjewski, Religie Czarnej Afryki, Kraków 2005, s. 31 n.

[2] Aszantowie przynależą do kultury Akan z Afryki Zachodniej. Zamieszkują Ghanę i Wybrzeże Kości Słoniowej. Posługują się dialektem twi asante języka akan. Należą do matrylinearnych, scentralizowanych ludów rolniczych obszarów leśnych. System religijny charakteryzuje się wiarą w Istotę Najwyższą – boga Onyame. Jest on uważany za stwórcę i pana całego świata, od niego wywodzi się rzesza bóstw i duchów.

[3] H. Zimoń, Pojęcie i klasyfikacja rytuałów, w: K. Kowalik (red.), Tradycja i otwartość. Księga pamiątkowa poświęcona o. Profesorowi Stanisławowi Celestynowi Napiórkowskiemu, Lublin 1999, s. 111. Zob. też L. Honko, Zur Klassifikation der Riten, „Temenos” 11:1975, s. 61; V. W. Turner, Symbols in African Ritual, w: J. L. Dolgin, D. S. Kemnitzer, D. M. Schneider (eds.), Symbolic Anthropology. A Reader in the Study of Symbols and Meanings, New York 1977, s. 183 n.

[4] Zimoń, Pojęcie i klasyfikacja, s. 114. Zob. też C. Bell, Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice, New York 1992, s. 182-187; M. Buchowski, Magia i rytuał, Warszawa 1993, s. 109 n.

[5] M. T. Douglas, Natural Symbols. Explorations in Cosmology, London 1970, s. 20.

[6] Zimoń, Pojęcie i klasyfikacja, s. 114. Zob. też E. R. Leach, Ritual, w: International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, Ed. D. L. Sills, Vol. 13, New York 1968, s. 523 n.

[7] Zimoń, Pojęcie i klasyfikacja, s. 117. Zob. także tenże, Klasyfikacja rytuałów, „Collectanea Theologica” 68:1998 nr 1, s. 185.

[8] Zob. Zimoń, Klasyfikacja rytuałów, s. 186 n.; tenże, Pojęcie i klasyfikacja, s. 118 n.

[9] Termin „rytuały przejścia” wprowadził do literatury francuski etnolog Arnold van Gennep, Les rites de passage, Paris 1909, s. 4.

[10] Tamże s. 1-5. Zob. również H. Czerwińska-Burszta, Teoria rytów przejścia Arnolda van Gennepa i jej recepcja na gruncie strukturalistycznym, „Lud” 70:1986, s. 52.

[11] Van Gennep, Les rites, s. 14, 27. Zob. też Zimoń, Pojęcie i klasyfikacja, s. 119 n.; Honko, Zur Klassifikation der Riten, s. 68 n.; E. Norbeck, Religion in Primitive Society, New York 1961, s. 141 n.; J. K. Olupona, Rituals in African Traditional Religion. A Phenomenological Perspective, „Orita” 22:1990 nr 1, s. 4.

[12] R. S. Rattray, Ashanti, Oxford 1923, s. 50 n. Zob. też W. Mrozek, Kult ntoro a struktura społeczna ludu Aszanti w Ghanie, Lublin 1993, s. 52 n. (mpsBKUL).

[13] A. C. Denteh, Birth Rites of the Akans, „Research Review” 3:1967 nr 3, s. 78 n.

[14] R. S. Rattray, Religion and Art in Ashanti, London 1927, s. 56 n

[15] Denteh, Birth Rites, s. 79.

[16] Nakaz ten wiąże się z tabu bogini ziemi Asase Yaa. Zob. P. Sarpong, Ghana in Retrospect. Some Aspects of Ghanaian Culture, Accra 1974, s. 18.

[17] Rattray, Religion and Art, s. 58 n.

[18] Denteh, Birth Rites, s. 79.

[19] Rattray (Religion and Art., s. 61) odkrył kości dzieci na jednym z wysypisk.

[20] Nazywane tak ze względu na formę pochówku. Aszantowie wierzą, że podjęcie pełnej formy pogrzebu, skutkowałoby bezpłodnością matki. Rattray, Religion and Art, s. 61.

[21] Tamże.

[22] Tamże, s. 64.

[23] Tamże, s. 65.

[24] P. Sarpong, Girl’s Nubility Rites in Ashanti, Tema-Ulm 1991, s. 11. Zob. też Rattray, Religion and Art, s. 69.

[25] J. G. Christaller (A Dictionary of the Asante and Fante Language Called tshi, Basel 1881, s. 46) podaje czasownik „obra” jako eufemistyczne określenie menstruacji. Sarpong (Girls’ Nubility Rites, s. 21) przytacza tekst takiej pieśni.

[26] Tekst modlitwy zob. Rattray, Religion and Art, s. 70.

[27] Rattray, Religion and Art, s. 71.

[28] Włosy są przechowywane na wypadek śmierci dziewczyny daleko od domu, wtedy rytuały pochówkowe sprawowane są nad nimi na zasadzie pars pro toto. Sarpong, Girls’ Nubility Rites, s. 27.

[29] Rattray, Religion and Art, s. 73.

[30] Tamże, s. 74.

[31] Tamże, s. 75.

[32] Sarpong, Girls’ Nubility Rites, s. 14 n.

[33] Tamże, s. 46.

[34] Rattray, Religion and Art, s. 106

[35] Christaller, A Dictionary, s. 566.

[36] P. Obeng, Asante Catholicism. Religious and Cultural Reproduction among the Akan of Ghana, Leiden 1996, s. 83 n.

[37] S. van der Geest, The Image of Death in Akan Highlife Songs of Ghana, „Research in African Literatures” 11:1980 nr 2, s. 163.

[38] J. H. K. Nketia, Funeral Dirges of the Akan People, Achimota 1955, s. 2.

[39] Rattray, Religion and Art, s. 147 n. Zob. też M. J. Field, Akim-Kotoku. An Oman of the Gold Coast, London 1948, s. 138-150; Nketia, Funeral Dirges, s. 2 n.

[40] Obeng, Asante Catholicism, s. 84. Zob. też K. Arhin, The Economic Implications of Transformations in Akan Funeral Rites, „Africa” 64:1994 nr 3, s. 310.

[41] Nketia, Funeral Dirges, s. 18.

[42] G. P. Hagan, A Note on Akan Colour Symbolism, „Research Review” 7:1970 nr 1, s. 8 n.

[43] Nketia, Funeral Dirges, s. 10 n. Zob. też Arhin, The Economic Implications, Appendix, s. 318 n.

[44] Nketia, Funeral Dirges, s. 44, 49.

[45] Obeng, Asante Catholicism, s. 86.

[46] P. A. Twumasi, Funeral Customs in Ashanti and Brong Ahafo Regions, w: D. K. Foawoo i in. (ed.), Funeral Customs in Ghana. A Preliminary Report, Legon 1977, s. 115 n. (mpsBUGh).

[47] Nketia, Funeral Dirges, s. 15 n. Zob. też Twumasi, Funeral Customs, s. 110 n.

[48] K. A. Opoku, Training the Priestess at the Akonnedi Shrine, „Research Review” 6:1970, s. 43 n.

[49] Zob. M. Gilbert, The Person of the King: Ritual and Power in Ghanaian State, w: D. Cannadine, S. Price (ed.), Ritual and Royalty. Power and Ceremonial in Traditional Societies, Cambridge 1987, s. 289-330; G. P. Hagan, The Golden Stool and the Oaths to the King of Ashanti, „Research Review” 4:1968 nr 3, s. 5-18.

[2] Aszantowie przynależą do kultury Akan z Afryki Zachodniej. Zamieszkują Ghanę i Wybrzeże Kości Słoniowej. Posługują się dialektem twi asante języka akan. Należą do matrylinearnych, scentralizowanych ludów rolniczych obszarów leśnych. System religijny charakteryzuje się wiarą w Istotę Najwyższą – boga Onyame. Jest on uważany za stwórcę i pana całego świata, od niego wywodzi się rzesza bóstw i duchów.

[3] H. Zimoń, Pojęcie i klasyfikacja rytuałów, w: K. Kowalik (red.), Tradycja i otwartość. Księga pamiątkowa poświęcona o. Profesorowi Stanisławowi Celestynowi Napiórkowskiemu, Lublin 1999, s. 111. Zob. też L. Honko, Zur Klassifikation der Riten, „Temenos” 11:1975, s. 61; V. W. Turner, Symbols in African Ritual, w: J. L. Dolgin, D. S. Kemnitzer, D. M. Schneider (eds.), Symbolic Anthropology. A Reader in the Study of Symbols and Meanings, New York 1977, s. 183 n.

[4] Zimoń, Pojęcie i klasyfikacja, s. 114. Zob. też C. Bell, Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice, New York 1992, s. 182-187; M. Buchowski, Magia i rytuał, Warszawa 1993, s. 109 n.

[5] M. T. Douglas, Natural Symbols. Explorations in Cosmology, London 1970, s. 20.

[6] Zimoń, Pojęcie i klasyfikacja, s. 114. Zob. też E. R. Leach, Ritual, w: International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, Ed. D. L. Sills, Vol. 13, New York 1968, s. 523 n.

[7] Zimoń, Pojęcie i klasyfikacja, s. 117. Zob. także tenże, Klasyfikacja rytuałów, „Collectanea Theologica” 68:1998 nr 1, s. 185.

[8] Zob. Zimoń, Klasyfikacja rytuałów, s. 186 n.; tenże, Pojęcie i klasyfikacja, s. 118 n.

[9] Termin „rytuały przejścia” wprowadził do literatury francuski etnolog Arnold van Gennep, Les rites de passage, Paris 1909, s. 4.

[10] Tamże s. 1-5. Zob. również H. Czerwińska-Burszta, Teoria rytów przejścia Arnolda van Gennepa i jej recepcja na gruncie strukturalistycznym, „Lud” 70:1986, s. 52.

[11] Van Gennep, Les rites, s. 14, 27. Zob. też Zimoń, Pojęcie i klasyfikacja, s. 119 n.; Honko, Zur Klassifikation der Riten, s. 68 n.; E. Norbeck, Religion in Primitive Society, New York 1961, s. 141 n.; J. K. Olupona, Rituals in African Traditional Religion. A Phenomenological Perspective, „Orita” 22:1990 nr 1, s. 4.

[12] R. S. Rattray, Ashanti, Oxford 1923, s. 50 n. Zob. też W. Mrozek, Kult ntoro a struktura społeczna ludu Aszanti w Ghanie, Lublin 1993, s. 52 n. (mpsBKUL).

[13] A. C. Denteh, Birth Rites of the Akans, „Research Review” 3:1967 nr 3, s. 78 n.

[14] R. S. Rattray, Religion and Art in Ashanti, London 1927, s. 56 n

[15] Denteh, Birth Rites, s. 79.

[16] Nakaz ten wiąże się z tabu bogini ziemi Asase Yaa. Zob. P. Sarpong, Ghana in Retrospect. Some Aspects of Ghanaian Culture, Accra 1974, s. 18.

[17] Rattray, Religion and Art, s. 58 n.

[18] Denteh, Birth Rites, s. 79.

[19] Rattray (Religion and Art., s. 61) odkrył kości dzieci na jednym z wysypisk.

[20] Nazywane tak ze względu na formę pochówku. Aszantowie wierzą, że podjęcie pełnej formy pogrzebu, skutkowałoby bezpłodnością matki. Rattray, Religion and Art, s. 61.

[21] Tamże.

[22] Tamże, s. 64.

[23] Tamże, s. 65.

[24] P. Sarpong, Girl’s Nubility Rites in Ashanti, Tema-Ulm 1991, s. 11. Zob. też Rattray, Religion and Art, s. 69.

[25] J. G. Christaller (A Dictionary of the Asante and Fante Language Called tshi, Basel 1881, s. 46) podaje czasownik „obra” jako eufemistyczne określenie menstruacji. Sarpong (Girls’ Nubility Rites, s. 21) przytacza tekst takiej pieśni.

[26] Tekst modlitwy zob. Rattray, Religion and Art, s. 70.

[27] Rattray, Religion and Art, s. 71.

[28] Włosy są przechowywane na wypadek śmierci dziewczyny daleko od domu, wtedy rytuały pochówkowe sprawowane są nad nimi na zasadzie pars pro toto. Sarpong, Girls’ Nubility Rites, s. 27.

[29] Rattray, Religion and Art, s. 73.

[30] Tamże, s. 74.

[31] Tamże, s. 75.

[32] Sarpong, Girls’ Nubility Rites, s. 14 n.

[33] Tamże, s. 46.

[34] Rattray, Religion and Art, s. 106

[35] Christaller, A Dictionary, s. 566.

[36] P. Obeng, Asante Catholicism. Religious and Cultural Reproduction among the Akan of Ghana, Leiden 1996, s. 83 n.

[37] S. van der Geest, The Image of Death in Akan Highlife Songs of Ghana, „Research in African Literatures” 11:1980 nr 2, s. 163.

[38] J. H. K. Nketia, Funeral Dirges of the Akan People, Achimota 1955, s. 2.

[39] Rattray, Religion and Art, s. 147 n. Zob. też M. J. Field, Akim-Kotoku. An Oman of the Gold Coast, London 1948, s. 138-150; Nketia, Funeral Dirges, s. 2 n.

[40] Obeng, Asante Catholicism, s. 84. Zob. też K. Arhin, The Economic Implications of Transformations in Akan Funeral Rites, „Africa” 64:1994 nr 3, s. 310.

[41] Nketia, Funeral Dirges, s. 18.

[42] G. P. Hagan, A Note on Akan Colour Symbolism, „Research Review” 7:1970 nr 1, s. 8 n.

[43] Nketia, Funeral Dirges, s. 10 n. Zob. też Arhin, The Economic Implications, Appendix, s. 318 n.

[44] Nketia, Funeral Dirges, s. 44, 49.

[45] Obeng, Asante Catholicism, s. 86.

[46] P. A. Twumasi, Funeral Customs in Ashanti and Brong Ahafo Regions, w: D. K. Foawoo i in. (ed.), Funeral Customs in Ghana. A Preliminary Report, Legon 1977, s. 115 n. (mpsBUGh).

[47] Nketia, Funeral Dirges, s. 15 n. Zob. też Twumasi, Funeral Customs, s. 110 n.

[48] K. A. Opoku, Training the Priestess at the Akonnedi Shrine, „Research Review” 6:1970, s. 43 n.

[49] Zob. M. Gilbert, The Person of the King: Ritual and Power in Ghanaian State, w: D. Cannadine, S. Price (ed.), Ritual and Royalty. Power and Ceremonial in Traditional Societies, Cambridge 1987, s. 289-330; G. P. Hagan, The Golden Stool and the Oaths to the King of Ashanti, „Research Review” 4:1968 nr 3, s. 5-18.

aktualna ocena | |

głosujących | |

Ocena |

bardzo słabe |

słabe |

średnie |

dobre |

super |

Ocena |

bardzo słabe |

słabe |

średnie |

dobre |

super |

Alfabet religii: UFO

Ufologia a religia. Ufologia a sekty... Warto przypomnieć, jak to jest z tą "wiarą" w obce istoty.

Alfabet religii: Sothis

Egipska bogini będąca personifikacją jednej z gwiazd widniejących na nieboskłonie.

Alfabet religii: Dzień Judaizmu

Jubileusz obwieszczajcie wyzwolenie w kraju dla wszystkich jego mieszkańców.

Alfabet religii: Słońcostanie

Czyli inaczej Szczodre Gody. Słowiańskie święto obchodzone w pierwszy dzień zimy.